John Peter Gabriel Muhlenberg

1746-1807

Clergyman, Revolutionary War General, Politician

Level 2 biography

Fast Facts

Peter Muhlenberg was a clergyman who became a general in the Revolutionary Army. He was Vice President of Pennsylvania under Benjamin Franklin, and served in Congress.

Born: Trappe, Pa. October 1, 1746.

Married: Anna Barbara (Hannah) Meyer November 6, 1770

Children: 4 sons, 2 daughters

Died: October 1, 1807

Level 2 biography

Fast Facts

Peter Muhlenberg was a clergyman who became a general in the Revolutionary Army. He was Vice President of Pennsylvania under Benjamin Franklin, and served in Congress.

Born: Trappe, Pa. October 1, 1746.

Married: Anna Barbara (Hannah) Meyer November 6, 1770

Children: 4 sons, 2 daughters

Died: October 1, 1807

Family Background

Peter Muhlenberg came from a family of people who acted on what they thought was right. His father was named Henry Melchior Muhlenberg. Peter’s father came to America from Germany as a missionary. He founded the Lutheran Church in America. Peter’s mother was named Anna Maria. Her father was Conrad Weiser. Weiser was an adventurous man, who negotiated several treaties with the Native Americans.

Early Life

John Peter Gabriel Muhlenberg was born in Trappe, Pa. on October 1, 1746. He was a shy, quiet boy. He loved to hunt and fish. He also liked to explore. He explored the woods around his home, and the nearby Schuylkill River.

Peter was the oldest of seven children. His younger brothers and sisters were named Betsy, Fredrick, Peggy, Henry Ernst, Polly, and Sally.

Once Peter was visiting his grandparents, Conrad and Anna Eve Weiser. Conrad Weiser was not at home. The family heard that there was an Indian attack nearby. Mrs. Weiser quickly took the children to safety in Reading. No one in the family was hurt. This event was exciting to Peter, and fired his imagination. Peter thought that he might like to be a soldier.

Peter was not a wonderful student. He loved to read, but he didn’t like to study. When Peter was 15 his family moved to Philadelphia. Peter was sent to The Academy there. His father was worried that the city boys would be a bad influence on Peter. He thought that it might be better to send Peter to school in Germany.

Schooling and Apprenticeship

Henry Muhlenberg had worked in an Orphan House in the town of Halle in Germany. He wrote to his friend Dr. Francke, and asked if the school would take Peter as a student. Dr. Franke wrote back and said that the school would be glad to take Peter and his two brothers as students. He said that he and some of the other elders of the church would be responsible for the boys while they were in Germany.

Travel at that time was not easy. On April 27, 1763 Peter, Fredrick and Henry Ernst said goodbye to their father. Their mother took them to the dock where they got on board a ship that was going to London. The crossing took 7 weeks. On June 15 the boys arrived in London and were met by their father’s old friend Ziegenhagen. He put them on a fishing boat, which took them to Rotterdam in the Netherlands on June 21. They traveled from there to Einbeck, Germany to visit their father’s family. A relative named Bense took them to the Orphan house around September 1.

Peter’s two brothers settled in to their new life fairly easily. Peter did not. He wanted a life of action. He thought that he might like to be a doctor, a soldier, or a merchant. It was obvious to his teachers that he was not a scholar.

Dr. Francke tried to find a place for Peter where he could learn about business. One of the other churchmen was named Archdeacon Niemeyer. He had a cousin who had a store in Lubeck. He sold both groceries and medicine. His name was Herr Leonhard Heinrich Niemeyer.

Herr Niemeyer said that he would be glad to take Peter as an apprentice for six years. He promised to give Peter room and board, and to teach him both about his business and how to be a good man. Dr. Francke would pay for Peter’s clothing from money sent by his father. In return Peter had certain duties. He was to arrange goods neatly in the shop, and to serve the customers politely. He was to pray to God every day. On Sunday he must go to church, and then read religious books for the rest of the day. He was not to go out without permission. He was given no money of his own.

The contract was signed on September 29, 1763. Peter started working at the shop with high hopes. Herr Niemeyer did not keep his promises. He did not teach Peter about medicine, or about bookkeeping. He took care of the medicines, and left Peter to handle the grocery shop. Peter had to work in the shop 7 days a week. He stood up all day, in an open shop, and worked until 10 o’clock at night. He learned how to run a grocery business in the first month. After that all he did was work hard.

The Niemeyers had promised that Peter would live with them. He lived in their home, but lived with the servants. He also had the job of cleaning everyone’s shoes.

Peter had only two shirts. The Niemeyers did not do their laundry very often. Peter wore the same shirt for 4-6 weeks. When the weather became cold Peter asked for warmer clothes. Mrs. Niemeyer told him that his father must send money, or Peter could go naked. All winter Peter worked in the wind and cold of the open shop in a thin shirt.

Peter had never met a dishonest person before, and he didn’t know what to do. He was not allowed to go out. He had no money. He was kept from talking to the customers. He could not write to his father to complain because Dr. Francke read all of his letters. If he complained, word would get back to Herr Niemeyer, who would treat him worse than ever. Also, Peter was embarrassed. He had upset his father when he did not do well in school. He thought that he had failed again.

Peter’s father did not know that Peter was in such a terrible situation. He sent generous amounts of money to Herr Niemeyer. He also sent presents requested by Herr Niemeyer. Peter never saw the money or the presents.

Finally Peter was able to tell a friend of his father’s, Rev. Pasche, about how he was being treated. When word got back to Dr. Francke, he said that Herr Niemeyer was doing a good job, and the problems were Peter’s fault. Herr Niemeyer tried to get Peter to sign a paper saying that he had been treated well. Peter refused.

Henry Muhlenberg was far away from his son. He could not check on things himself. He did think that something was very wrong. He asked for a new contract. Herr Niemeyer signed a new contract on July 16, 1766. He said that if he were paid 100 thalers (money) he would teach Peter bookkeeping. Once again he did not keep his promise.

Peter realized that his family was too far away to help him. He must solve his own problems. There was a soldier in Lubeck named Captain Fiser. He was recruiting soldiers to go to America to serve in a British regiment. Peter asked Captain Fiser to let him join the soldiers so he could go back to America. Captain Fiser could see that Peter was in trouble, and he was glad to help him. He agreed to sign Peter into the army as the “Secretary of the Regiment.” Peter could go to Philadelphia with the soldiers. He would be discharged as soon as he reached home.

On August 13 1766 Peter left the Niemeyer house at 4:30 in the morning. He went straight to the recruiting office and was sworn in as a British soldier. After he was sworn in, he sent a note to the Niemeyers telling them what he had done. When Herr Niemeyer got the note, he came to the recruiting office to bring Peter home. Captain Fiser refused to let Peter go unless he said that he wanted to. Peter made it very clear that he did not want to go home with Herr Niemeyer.

Herr Niemeyer wrote to Dr. Francke. He said Peter was a sinful boy. Dr. Francke wrote a nasty letter to Peter’s parents. They were shocked. Peter’s mother, Anna Maria, was so upset that she became sick. After this she started to have seizures.

Finding His Career

Peter arrived in Philadelphia on January 15, 1767. He was honorably discharged from the army right away. His father gave Captain Fiser 20 pounds in English money to pay for Peter’s expenses. The family was very glad to be together again.

Peter had enjoyed being in the army, but he didn’t want to stay there. He thought that he’d like to go into medicine, business, or perhaps be a minister like his father. Henry Muhlenberg sent his son to a private English school where he learned bookkeeping.

Now that he was an adult, Peter had to decide what job he wanted to do. One friend suggested that he run an alehouse, because he had learned how to serve liquor from Herr Niemeyer. No one liked that idea. Another friend suggested that Peter start a business selling groceries and medicines, like he had done in Germany. The medicines all came from Halle. Dr. Francke was still very angry with Peter, and said he would not send Peter any medicine. Still another friend suggested that Peter could be a missionary to the Six Nations. Peter’s father said that it was more likely that Peter would become like the Native Americans than that they would become like him.

None of the ideas seemed right. At last a Swedish Lutheran man, Provost Wrangle, offered to train Peter as a minister. This time Peter had a good man to work for. Provost Wrangle taught him about religion, and had him tutored in Latin and Greek. Peter studied sermons. After a few months, Peter was sent to a church to give a sermon that he had learned by heart. He did a good job, and was welcomed by the people of the church. Peter then preached in several other churches. Finally, on Good Friday of 1768 he preached in his father’s church, St. Michael’s. His father was so worried that he stayed home and prayed the whole time. The sermon was a success.

Peter became his father's assistant. He helped him with his congregations in Bedminster, Pennsylvania and New Germantown, New Jersey.

In 1770 Peter’s brothers came back from Germany. They were both ordained into the church. Peter stayed home to mind his father’s churches while the family went to the ordination ceremonies.

A Call to the Ministry

On May 4, 1771 a letter was written in Woodstock, Virginia that would change Peter’s life. This letter invited him to be the preacher at the church in Woodstock. The congregation there spoke both German and English. Since Peter did too, they thought that it would be a good fit. He would be paid 250 pounds each year, have a parsonage, and a 200-acre farm. There was only one condition. The official church in Virginia was the Church of England. Peter had to be ordained as an Anglican, or he would not be able to perform marriages or baptisms.

This was not a problem. There were no great differences between Lutherans and Anglicans. Peter left Philadelphia for England on the Pennsylvania Packet on March 2, 1772. He arrived in Dover, England on April 10, and took a coach to London. On Tuesday, April 21 he went to Mayfair Chapel and was ordained a deacon by the Bishop of Ely. On Saturday the 25th the Bishop of London ordained him as a priest in the King’s Chapel. Now he had what he needed to take his new job.

Peter had trouble getting passage back to America. He finally paid 25 guineas, and left Deptford on May 24 to sail to America. When he arrived home in Philadelphia, Peter sold his furniture and bought a sorrel horse. He traveled south toward his new job, stopping to visit his brother Frederick on the way.

A Minister in Virginia

Peter was happy in his new job. He made good friends among both the English speakers and the Germans. There were many people in the congregation who liked to hunt and fish, as he did. This may be how he met George Washington. He was interested in politics. He became a magistrate, and a member of the House of Burgesses. He liked to listen to what Patrick Henry had to say.

On November 6, 1770 Peter married Anna Barbara Meyer, whose father was a potter. Her name was Anna Barbara, but everyone called her Hannah.

Political Unrest

This was a difficult time for the colonies. The Boston Tea Party took place about a year after Peter arrived in Virginia. The British punished the people of Boston by closing the port as of June 1. In sympathy, the Virginia Assembly declared June 1 a day of mourning.

The people of Virginia were afraid that England might close ports in Virginia, too. On June 16 there was a meeting of people in Woodstock. They talked about how to protect themselves from action like that in Boston. Peter was the moderator of the meeting. The group drew up a series of Resolves, which said that they would not accept any imports from England. They wanted to meet with other groups in Virginia. A Convention was arranged for people from all over Virginia. It was to be held in Williamsburg from August 1 to 6. Peter was the representative for Dunmore County. Patrick Henry spoke at the convention. George Washington offered to raise 1000 men and to march on Boston.

Advice From His Father

That same month, August 1771, Peter’s father Henry was going on a long journey. Peter went back to Pennsylvania to see his father off. The two men had a long talk. Henry thought that all clergymen should be neutral. He felt that the colonies should work toward peace. He urged Peter not to rush into action. When Peter went home, he resigned from all of his political offices.

The Colonies Want Freedom

Peter could not stay out of the action for long. Matters with England became worse in the next few years. In January 1775 Peter was elected the Chairman of the Committee of Correspondence for Dunmore County. In June Virginia held a convention to decide how the people might get their rights and liberties. Peter went to this convention. It was here that Patrick Henry made his most famous speech. It ended with the words, “Give me liberty, or give me death.” His speech impressed Peter very much. He understood that matters were urgent. He could no longer follow his father’s way of neutrality. He knew that he must serve the fight for liberty either as a soldier or as a chaplain in the army.

The Decision to Fight

Peter went to another convention in Williamsburg on January 12, 1776. Here he was appointed a Colonel in the army. He was 29 years old.

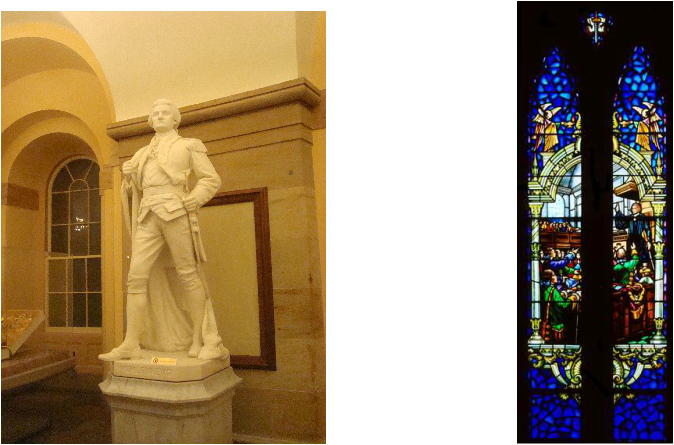

Peter returned to his church. He preached a farewell sermon. It was very dramatic. He said that there is a time to pray and a time to fight. The time had come to fight. Then he threw off his parson’s robes. Underneath his robes he wore his bright blue uniform. He stepped out of the church and ordered that the drum be beaten to invite men to join the army. Peter had become a soldier. 300 men enlisted that day. They became the 8th Virginia Regiment, known as “the German Regiment.”

Left: This statue, which stands inStatuary Hall in the Capitol building in Washington D. C. shows Peter Muhlenberg taking off his pastor's robe in preparation for being a soldier.

Right: Peter Muhlenberg preaching his last sermon. Stained glass window. Reproduced with permission from Muhlenberg Lutheran Church, Harrisonburg, VA.

Peter Muhlenberg, Commanding Officer

During the war of Independence, Peter Muhlenberg was a faithful, efficient officer. Both General Washington and General Steuben trusted him. He faced some amazing problems, but never lost heart. Here is a summary of Peter’s activities during the war.

Peter’s First Regiment

Peter trained his regiment well. They were sent to Charleston in June. On June 28 they fought the British, and kept them away from Fort Moultrie. Their next assignment was to go to Savannah. They were given no supplies or medicine. The area was swampy, the air unhealthy. In two months many men became sick. Peter developed a liver problem. It troubled him for the rest of his life. For the rest of the year the war did not go well. Even George Washington was discouraged.

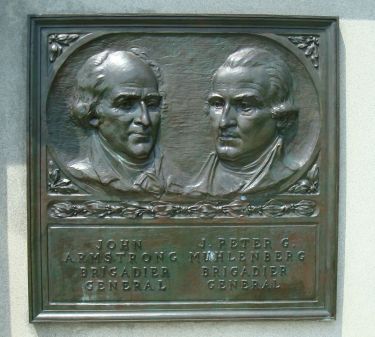

Brigadier General

In February 1777 Peter was promoted to Brigadier General. He was in charge of a brigade, which is made up of several regiments. Peter’s job was to train the troops and get them ready to fight. By May he had 2000 disciplined soldiers. He took them to Morristown. He tried to find the British to fight them. General Howe was the British commander. He kept moving his troops around, and was hard to follow.

Peter Muhlenberg was a good soldier. He understood that soldiers must work together to win a battle. He and his men often were in a supporting role, not the stars of the show. Peter’s men were at Chad’s Ford. They fought in the battles of Brandywine and Germantown. The colonists fought very well, but lost both battles.

General Washington needed a place for his soldiers to spend the winter. He asked Peter’s advice, since Peter knew the area well. Peter suggested a line from Reading through Allentown and Easton. There were plenty of houses there where the men could stay. He knew that the men would be comfortable and well fed. General Washington decided not to take this advice. General Howe had captured Philadelphia, and Washington wanted to keep an eye on him. He also wanted to cut General Howe’s men off from supplies of food. For these reasons he chose to take his men to Valley Forge.

All of this time, Peter was very close to home. His wife, Hannah, and two-year-old son Henry were staying with his parents at Trappe. Peter visited often at first. When the troops went to Valley Forge, only 7 miles from Trappe, Peter did not visit much at all. He knew that his visits put his family in danger, so he stayed away. He tried to convince his family to move to a safer area, but his mother refused to leave.

In June the British left Philadelphia. Peter and his men were at the Battle of Monmouth. Their job was to hold their position. Since their enemies ran, they never had to attack.

In 1778 Peter was headquartered at West Point. He advised General Washington about places to winter the troops. This time the General agreed with his suggestions.

Peter Muhlenberg had a strong sense of justice. He thought things should be fair. During 1778 he was concerned about his rank. He thought that it was unfair that General Woodford ranked above him. He worried about money. He hoped that he would be given some land in Ohio when the war was over to pay for his good work. Peter also was anxious about his family. His wife Hannah was at home in Woodstock and was expecting another baby. Peter was not allowed to leave his post to go to see her. Fortunately their friends took care of her. Their son, Charles Frederick, was born healthy and well.

During the winter of 1778, General Washington had put a circle of soldiers around New York to keep the British in, and to keep communication lines open between New England and the southern colonies. By May the British wanted to break through this line. They captured a place called Stony Point. In July Anthony Wayne recaptured Stony Point, but only held it for 24 hours. Peter Muhlenberg and his men were there, in reserve. They did not have much action for the rest of the year.

In June the British left Philadelphia. Peter and his men were at the Battle of Monmouth. Their job was to hold their position. Since their enemies ran, they never had to attack.

In 1778 Peter was headquartered at West Point. He advised General Washington about places to winter the troops. This time the General agreed with his suggestions.

Peter Muhlenberg had a strong sense of justice. He thought things should be fair. During 1778 he was concerned about his rank. He thought that it was unfair that General Woodford ranked above him. He worried about money. He hoped that he would be given some land in Ohio when the war was over to pay for his good work. Peter also was anxious about his family. His wife Hannah was at home in Woodstock and was expecting another baby. Peter was not allowed to leave his post to go to see her. Fortunately their friends took care of her. Their son, Charles Frederick, was born healthy and well.

During the winter of 1778, General Washington had put a circle of soldiers around New York to keep the British in, and to keep communication lines open between New England and the southern colonies. By May the British wanted to break through this line. They captured a place called Stony Point. In July Anthony Wayne recaptured Stony Point, but only held it for 24 hours. Peter Muhlenberg and his men were there, in reserve. They did not have much action for the rest of the year.

Back to Virginia

In December of 1779, General Washington asked Peter to go to Virginia to take command of the troops there. The winter was very bad, and it was hard to travel. Peter did not arrive in Virginia until March of 1780. By that time General Frederick von Steuben had taken command. Peter worked as his second in command.

Peter now had a new, difficult job. He was ordered to raise troops in Virginia. Virginia did not have an army, and had no draft law. (A law to order people to join the army.) Another problem was that Peter was trying to please two bosses. Thomas Jefferson was the governor of Virginia. He expected Peter to follow his orders. Peter also was under the command of George Washington. It was hard to please both men at once.

On May 12 the British captured Charleston, Virginia. Suddenly, things changed. Virginia quickly passed laws to draft men into the army. Peter now had plenty of men to train. By June 19 he had 2500 men who were ready to fight. By September he had over 5000 more.

The problem now was that there were not enough arms and supplies. There were only 4000 guns for all of these soldiers. There were only 2 surgeons to take care of sick and wounded men. There were no tents, blankets, kettles, or shoes. There were only small amounts of food, medical supplies, and ammunition. General Gates told Peter to send the troops without supplies. Washington hoped that the French would provide supplies, but they did not.

In October the British fleet came to Virginia. Peter bought 800 soldiers to meet them, but the British ships sailed away. Since there were no supplies, Peter took his men to Chesterfield Court House where there were barracks where the men could stay.

Chasing Benedict Arnold

In early 1782 Peter Muhlenberg finally took some leave and went home to see his family. He was only at home for three days before he was called back to duty. He was ordered to go after Benedict Arnold. Arnold had been a General in the American army. He had betrayed the Americans, and gone to fight for the British. Governor Jefferson was anxious to capture and punish him. He offered a reward of 5000 guineas. Peter set a trap for Arnold, but he didn’t take the bait.

Lack of Supplies Leads to Retreats

Peter’s men were unhappy. They were tired of having no supplies. The French General Lafayette came to visit Peter in March, and saw that there were too few men to attack the British. By April Peter had only 700 men left. He had guns, but the rain had ruined them. In April the British came out of Portsmouth and went after Peter and his men. With no guns, they could not stand and fight. The British came up the James River in flat- bottomed boats. Peter’s cavalrymen watched where the British were going, and reported their position. General Steuben arranged to meet Peter and his men at a spot right outside Petersburg. On April 25 the British and Americans fought at Petersburg. Peter’s men fought bravely. There were more British than Americans, so the Americans had to retreat.

Joining Lafayette

That afternoon Peter took his men to Richmond. On the 29th General Lafayette joined them with more men. Lafayette was the general in command. Peter was the senior commander under him, with about 1000 light infantry. Lafayette used Muhlenberg’s troops as the “fangs” of his army. Anthony Wayne was also in the area with his men. When the British attacked Wayne’s men on July 6, Peter Muhlenberg’s men came and rescued them.

Yorktown

General Washington had a plan. He decided to pretend to attack New York, while really going to attack Yorktown. Peter Muhlenberg’s job was to stop General Cornwallis and his men from crossing the Roanoke River.

The siege of Yorktown began on September 28. This meant that the Americans had Yorktown surrounded. Peter Muhlenberg and his men were right in the front. When the order came to attack Yorktown, Peter’s men attacked and captured Redoubt 10, an important step toward taking the city. General Cornwallis surrendered on October 19.

After the battle, a report was written for General Washington. The man who wrote it was named Alexander Hamilton. Hamilton had arrived just before the battle. In his report, he made it seem like he was the hero who had led the men to victory. Peter Muhlenberg, who had been there the whole time, was hardly mentioned. Peter’s feelings were hurt. He was exhausted, and sick with a fever. He asked for permission to go home. He went to Woodstock and stayed there. Once again, he felt that he was not treated fairly.

While Peter was at home, the Virginia army began to break up and go home. In December General Greene went to see Peter and asked him to come back. In January both sides signed papers for a peace. Peter returned to duty in February. He was told to recruit more men, but it wasn’t really necessary. Peace was proclaimed on April 19, and the Treaty of Paris, which formally ended the war, was signed on September 5, 1783.

After the War

Peter was promoted to Major General on September 30, 1783. On November 3 he retired from the army. He also retired from the ministry. Peter took his family back to Pennsylvania that same month.

Peter was welcomed warmly in Pennsylvania. The German people of Pennsylvania saw him as a hero of the Revolution, placing right after George Washington. He was tall, handsome, and had good manners. He was very popular.

Peter had been so active for so long that he was soon restless. He thought that it might be a good idea to move to the Ohio frontier. Part of his payment for his service in the Virginia Army was some land in Ohio. He owned 11,662 2/3 acres of land in Sciota, 160 miles west of Fort Pittsburgh. Peter thought that he would like to see his land. The Virginia Assembly asked him to look for more land while he was out there.

A Journey to Ohio.

The winter of 1783-1784 was terrible. In spite of this, and though he was still weak from being sick, Peter wanted to make an early start. He left home on February 22 and started to travel west. Heavy snow delayed him. His friend, Captain Paske¢, joined him at Carlisle. They reached Fort Pitt on March 10. Once again there were delays. On March 31, Peter and a group of other men got on board flat-bottomed boats and started down the river. One of the boats was named the Muhlenberg, in honor of Peter. They took horses, flour, bacon, and other goods. On the way the group saw a lot of game, and many species of fish. They reached Louisville on April 11. The country was beautiful. The town was tiny, with seven huts, a courthouse, and a jail. Peter wanted to explore the area, but learned that no treaty had been made with the Native Americans who lived there. He met with Cornstalk and other warriors. They did not welcome settlers. Peter knew better than to force the issue. He decided to return home without looking over the land. He arrived home on June 25. Later that summer Peter went before Congress. He explained that the land could only be settled peacefully if a treaty were signed. Congress decided to wait for a treaty before trying to settle the land.

Working in Politics

Now Peter knew that he would be staying in Pennsylvania. He ran for office in Montgomery County in 1785. Respected by everyone, he was elected to Pennsylvania’s Supreme Executive Council for a three-year term. He also ran for the position of Vice President of Pennsylvania. He lost to Charles Biddle by three votes.

Peter was a moderate man in politics. He did not go to the Constitutional Convention, but he worked to have the Constitution ratified. When Pennsylvania ratified the Constitution in 1787, there was a large parade. Peter marched in this parade, carrying a blue flag with silver letters. On the flag were the words “Seventeenth of September, 1787.”

In the fall of 1787 Peter was elected Vice President of Pennsylvania. Benjamin Franklin was the President. Because Benjamin Franklin was in poor health, Peter took over many of his official duties. Three issues were resolved under Peter’s leadership. The first was the purchase of the Erie Triangle in the northwestern corner of the state. This gave Pennsylvania a port on Lake Erie. The second was concern over the Hessian fly, which was an insect that destroyed wheat. The third had to do with the Wyoming Controversy, when Connecticut tried to claim part of Pennsylvania. In all three cases, Peter Muhlenberg was the person who signed the legal documents.

George Washington became President on April 30 of 1789. Each state elected men to go to Congress. Pennsylvania elected Peter to the House of Representatives. He served in the 1st, 3rd, and 6th sessions of Congress. The whole time that he was in Congress, he never made a single speech.

Peter was restless. In 1797, between his service in the third and sixth Congress, he took another trip to Ohio. He said he was tired of politics. People asked him to run for Governor of Pennsylvania, but he refused.

The Election of 1801

In February of 1801 Thomas Jefferson and Aaron Burr ran for President. Each received 73 votes. It was a tie. The House of Representatives had to break this tie. The constitution said that one man must have 9 states vote for him to win. When the House voted, neither man had nine votes. They voted again and again. They voted from February 11 to February 17. There were 35 ballots. Neither man had the nine votes he needed.

Some people suggested that Congress should just name somebody to be President. People in Washington were afraid that this might happen. They asked Governor McKean of Pennsylvania to have the soldiers of the Pennsylvania Militia ready. They could march to Washington if someone tried to take over the government. The Governor asked Peter Muhlenberg to lead these troops if it was necessary.

At last on the 36th ballot, there was a change in the voting. Thomas Jefferson received 10 votes, Aaron Burr 4. Jefferson became President, and there was no need for soldiers.

Peter was elected to the Seventh session of Congress as a Senator. He served for two days, March 4 and 5. Then he resigned.

Later Life

All of this time, Peter had kept his position as a Major General of the Second Division in the militia. He was in charge of soldiers from Bucks and Montgomery County.

In June 1801 Peter was given the job of Supervisor of United States Customs in the District of Pennsylvania. When he took this job, he resigned from the army.

Peter still did not like to sit still. In 1803 he was appointed the Collector of the Port in Philadelphia. He bought some land in Pasyunk on the Schuylkill River. The fishing was good there.

Peter’s wife Hannah became very sick. She grew weaker each day. Peter sat beside her bed every night for two months. Finally Hannah died during the night of October 27-28, 1806. She was buried at Trappe beside Peter’s parents.

Peter was exhausted. His liver problem, which had started during the war, bothered him again. He knew that he was ill. He made a will on July 18, 1807.

October 1, 1807 was Peter Muhlenberg’s 61st birthday. He died on that day. He was buried in Trappe next to his wife. His tombstone says:

“He was Brave in the field, Faithful

in the Cabinet, Honorable in

all his transactions, a Sincere Friend

and an Honest Man.”

Where we see his name today

There is a Peter Muhlenberg Middle School in Woodstock, VA.

Muhlenberg Lutheran Church in Harrisonburg, Virginia is named in honor of Peter Muhlenberg.

In Washington D.C. there is a National Statuary Hall. Each state has two statues to represent their people. Pennsylvania’s two statues are of Thomas Edison and Peter Muhlenberg. Blanche Nevin sculpted the Muhlenberg statue. See picture above

At Valley Forge, Pa. there is a Brigade Marker commemorating the Muhlenberg Brigade.

In December of 1779, General Washington asked Peter to go to Virginia to take command of the troops there. The winter was very bad, and it was hard to travel. Peter did not arrive in Virginia until March of 1780. By that time General Frederick von Steuben had taken command. Peter worked as his second in command.

Peter now had a new, difficult job. He was ordered to raise troops in Virginia. Virginia did not have an army, and had no draft law. (A law to order people to join the army.) Another problem was that Peter was trying to please two bosses. Thomas Jefferson was the governor of Virginia. He expected Peter to follow his orders. Peter also was under the command of George Washington. It was hard to please both men at once.

On May 12 the British captured Charleston, Virginia. Suddenly, things changed. Virginia quickly passed laws to draft men into the army. Peter now had plenty of men to train. By June 19 he had 2500 men who were ready to fight. By September he had over 5000 more.

The problem now was that there were not enough arms and supplies. There were only 4000 guns for all of these soldiers. There were only 2 surgeons to take care of sick and wounded men. There were no tents, blankets, kettles, or shoes. There were only small amounts of food, medical supplies, and ammunition. General Gates told Peter to send the troops without supplies. Washington hoped that the French would provide supplies, but they did not.

In October the British fleet came to Virginia. Peter bought 800 soldiers to meet them, but the British ships sailed away. Since there were no supplies, Peter took his men to Chesterfield Court House where there were barracks where the men could stay.

Chasing Benedict Arnold

In early 1782 Peter Muhlenberg finally took some leave and went home to see his family. He was only at home for three days before he was called back to duty. He was ordered to go after Benedict Arnold. Arnold had been a General in the American army. He had betrayed the Americans, and gone to fight for the British. Governor Jefferson was anxious to capture and punish him. He offered a reward of 5000 guineas. Peter set a trap for Arnold, but he didn’t take the bait.

Lack of Supplies Leads to Retreats

Peter’s men were unhappy. They were tired of having no supplies. The French General Lafayette came to visit Peter in March, and saw that there were too few men to attack the British. By April Peter had only 700 men left. He had guns, but the rain had ruined them. In April the British came out of Portsmouth and went after Peter and his men. With no guns, they could not stand and fight. The British came up the James River in flat- bottomed boats. Peter’s cavalrymen watched where the British were going, and reported their position. General Steuben arranged to meet Peter and his men at a spot right outside Petersburg. On April 25 the British and Americans fought at Petersburg. Peter’s men fought bravely. There were more British than Americans, so the Americans had to retreat.

Joining Lafayette

That afternoon Peter took his men to Richmond. On the 29th General Lafayette joined them with more men. Lafayette was the general in command. Peter was the senior commander under him, with about 1000 light infantry. Lafayette used Muhlenberg’s troops as the “fangs” of his army. Anthony Wayne was also in the area with his men. When the British attacked Wayne’s men on July 6, Peter Muhlenberg’s men came and rescued them.

Yorktown

General Washington had a plan. He decided to pretend to attack New York, while really going to attack Yorktown. Peter Muhlenberg’s job was to stop General Cornwallis and his men from crossing the Roanoke River.

The siege of Yorktown began on September 28. This meant that the Americans had Yorktown surrounded. Peter Muhlenberg and his men were right in the front. When the order came to attack Yorktown, Peter’s men attacked and captured Redoubt 10, an important step toward taking the city. General Cornwallis surrendered on October 19.

After the battle, a report was written for General Washington. The man who wrote it was named Alexander Hamilton. Hamilton had arrived just before the battle. In his report, he made it seem like he was the hero who had led the men to victory. Peter Muhlenberg, who had been there the whole time, was hardly mentioned. Peter’s feelings were hurt. He was exhausted, and sick with a fever. He asked for permission to go home. He went to Woodstock and stayed there. Once again, he felt that he was not treated fairly.

While Peter was at home, the Virginia army began to break up and go home. In December General Greene went to see Peter and asked him to come back. In January both sides signed papers for a peace. Peter returned to duty in February. He was told to recruit more men, but it wasn’t really necessary. Peace was proclaimed on April 19, and the Treaty of Paris, which formally ended the war, was signed on September 5, 1783.

After the War

Peter was promoted to Major General on September 30, 1783. On November 3 he retired from the army. He also retired from the ministry. Peter took his family back to Pennsylvania that same month.

Peter was welcomed warmly in Pennsylvania. The German people of Pennsylvania saw him as a hero of the Revolution, placing right after George Washington. He was tall, handsome, and had good manners. He was very popular.

Peter had been so active for so long that he was soon restless. He thought that it might be a good idea to move to the Ohio frontier. Part of his payment for his service in the Virginia Army was some land in Ohio. He owned 11,662 2/3 acres of land in Sciota, 160 miles west of Fort Pittsburgh. Peter thought that he would like to see his land. The Virginia Assembly asked him to look for more land while he was out there.

A Journey to Ohio.

The winter of 1783-1784 was terrible. In spite of this, and though he was still weak from being sick, Peter wanted to make an early start. He left home on February 22 and started to travel west. Heavy snow delayed him. His friend, Captain Paske¢, joined him at Carlisle. They reached Fort Pitt on March 10. Once again there were delays. On March 31, Peter and a group of other men got on board flat-bottomed boats and started down the river. One of the boats was named the Muhlenberg, in honor of Peter. They took horses, flour, bacon, and other goods. On the way the group saw a lot of game, and many species of fish. They reached Louisville on April 11. The country was beautiful. The town was tiny, with seven huts, a courthouse, and a jail. Peter wanted to explore the area, but learned that no treaty had been made with the Native Americans who lived there. He met with Cornstalk and other warriors. They did not welcome settlers. Peter knew better than to force the issue. He decided to return home without looking over the land. He arrived home on June 25. Later that summer Peter went before Congress. He explained that the land could only be settled peacefully if a treaty were signed. Congress decided to wait for a treaty before trying to settle the land.

Working in Politics

Now Peter knew that he would be staying in Pennsylvania. He ran for office in Montgomery County in 1785. Respected by everyone, he was elected to Pennsylvania’s Supreme Executive Council for a three-year term. He also ran for the position of Vice President of Pennsylvania. He lost to Charles Biddle by three votes.

Peter was a moderate man in politics. He did not go to the Constitutional Convention, but he worked to have the Constitution ratified. When Pennsylvania ratified the Constitution in 1787, there was a large parade. Peter marched in this parade, carrying a blue flag with silver letters. On the flag were the words “Seventeenth of September, 1787.”

In the fall of 1787 Peter was elected Vice President of Pennsylvania. Benjamin Franklin was the President. Because Benjamin Franklin was in poor health, Peter took over many of his official duties. Three issues were resolved under Peter’s leadership. The first was the purchase of the Erie Triangle in the northwestern corner of the state. This gave Pennsylvania a port on Lake Erie. The second was concern over the Hessian fly, which was an insect that destroyed wheat. The third had to do with the Wyoming Controversy, when Connecticut tried to claim part of Pennsylvania. In all three cases, Peter Muhlenberg was the person who signed the legal documents.

George Washington became President on April 30 of 1789. Each state elected men to go to Congress. Pennsylvania elected Peter to the House of Representatives. He served in the 1st, 3rd, and 6th sessions of Congress. The whole time that he was in Congress, he never made a single speech.

Peter was restless. In 1797, between his service in the third and sixth Congress, he took another trip to Ohio. He said he was tired of politics. People asked him to run for Governor of Pennsylvania, but he refused.

The Election of 1801

In February of 1801 Thomas Jefferson and Aaron Burr ran for President. Each received 73 votes. It was a tie. The House of Representatives had to break this tie. The constitution said that one man must have 9 states vote for him to win. When the House voted, neither man had nine votes. They voted again and again. They voted from February 11 to February 17. There were 35 ballots. Neither man had the nine votes he needed.

Some people suggested that Congress should just name somebody to be President. People in Washington were afraid that this might happen. They asked Governor McKean of Pennsylvania to have the soldiers of the Pennsylvania Militia ready. They could march to Washington if someone tried to take over the government. The Governor asked Peter Muhlenberg to lead these troops if it was necessary.

At last on the 36th ballot, there was a change in the voting. Thomas Jefferson received 10 votes, Aaron Burr 4. Jefferson became President, and there was no need for soldiers.

Peter was elected to the Seventh session of Congress as a Senator. He served for two days, March 4 and 5. Then he resigned.

Later Life

All of this time, Peter had kept his position as a Major General of the Second Division in the militia. He was in charge of soldiers from Bucks and Montgomery County.

In June 1801 Peter was given the job of Supervisor of United States Customs in the District of Pennsylvania. When he took this job, he resigned from the army.

Peter still did not like to sit still. In 1803 he was appointed the Collector of the Port in Philadelphia. He bought some land in Pasyunk on the Schuylkill River. The fishing was good there.

Peter’s wife Hannah became very sick. She grew weaker each day. Peter sat beside her bed every night for two months. Finally Hannah died during the night of October 27-28, 1806. She was buried at Trappe beside Peter’s parents.

Peter was exhausted. His liver problem, which had started during the war, bothered him again. He knew that he was ill. He made a will on July 18, 1807.

October 1, 1807 was Peter Muhlenberg’s 61st birthday. He died on that day. He was buried in Trappe next to his wife. His tombstone says:

“He was Brave in the field, Faithful

in the Cabinet, Honorable in

all his transactions, a Sincere Friend

and an Honest Man.”

Where we see his name today

There is a Peter Muhlenberg Middle School in Woodstock, VA.

Muhlenberg Lutheran Church in Harrisonburg, Virginia is named in honor of Peter Muhlenberg.

In Washington D.C. there is a National Statuary Hall. Each state has two statues to represent their people. Pennsylvania’s two statues are of Thomas Edison and Peter Muhlenberg. Blanche Nevin sculpted the Muhlenberg statue. See picture above

At Valley Forge, Pa. there is a Brigade Marker commemorating the Muhlenberg Brigade.

Muhlenberg College in Pennsylvania is named for Peter’s father, Henry Melchior Muhlenberg. In the Martin Art Gallery on the college campus there is a portrait of Peter Muhlenberg.

Reading Level 6.2. Photographs by M and T. Yates Portrait of Peter Muhlenberg reproduced with permission from the Martin Art Gallery, Muhlenberg College, Allentown Pa.

Reading Level 6.2. Photographs by M and T. Yates Portrait of Peter Muhlenberg reproduced with permission from the Martin Art Gallery, Muhlenberg College, Allentown Pa.