Christopher Ludwick

1720-1801

Soldier, Baker, Patriot, Philanthropist

Level 2 biography

Level 2 biography

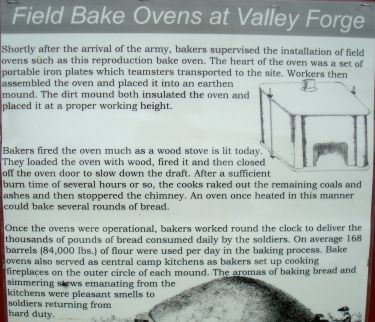

This mound is actually a bake oven of the kind used by George Washington's army at Valley Forge

to bake bread for the United States army. Christopher Ludwick was Washington's Baker General,

which means he was in charge of all of the army's bakers, and responsible for the quality of bread

that was produced.

Fast Facts

Christopher Ludwick was the Superintendent of Bakers for the Continental Army during the Revolutionary War.

Born: October 17, 1720, at Griessen in Hesse Darmstadt in Germany

Died: June 17, 1801 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Married:

1. Catharine England. Died September 21, 1796

2. Sophia Binder married 1798

No children

Christopher Ludwick was the Superintendent of Bakers for the Continental Army during the Revolutionary War.

Born: October 17, 1720, at Griessen in Hesse Darmstadt in Germany

Died: June 17, 1801 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Married:

1. Catharine England. Died September 21, 1796

2. Sophia Binder married 1798

No children

Early Life

Christopher Ludwick was born in the town of Griessen in the province of Hesse Darmstadt in Germany on October 17, 1720. His father was a baker. Christopher learned the baking trade as soon as he was old enough to work. When he was 14 he went a free school where he learned to read, write, and work with numbers. He also learned about the Lutheran faith.

Soldier

At age 17 Christopher Ludwick joined the Austrian army as a private. From 1737 to 1740 he fought in the war against Turkey. When the war was over Christopher was part of a group of 100 men who were far from home. They were ordered to march to Vienna across barren, cold country. The march was very hard. On the way 75 of the men died. Christopher was one of the 25 men who lived to reach Vienna. He stayed in Vienna for a few weeks. During that time the Commissary General (man in charge of supplies) for the Austrian Army was executed for being dishonest. This made a big impression on the young man. From Vienna, Christopher traveled to Prague. He was in the town when the French surrounded it. The town was under siege for 17 weeks. Prague surrendered to the French in 1741. When he was free to travel, Christopher joined the Prussian Army.

Sailor and Baker

After a time Christopher had enough of being a soldier. He went to London and took a job as a baker on the ship The Duke of Cumberland. The commander of the ship was Admiral Boscawen. The ship sailed to a number of ports. In 1745 The Duke of Cumberland returned to London. Christopher Ludwick was paid his wages. He received 111 guineas and 1 English crown. Christopher used the money to go back to Germany. He wanted to visit his father. When he reached his home he learned that his father had died. Christopher’s father left him his whole estate. Christopher sold what his father had left him for 500 guilders. He took the money and part of his wages, and went back to London. He decided to enjoy himself. He had a good time, and spent all of his money. When his money was gone, Christopher Ludwick went to sea again. This time he worked as a sailor. His ship sailed from London to Holland, Ireland, and the West Indies. Christopher saved the money he earned on this trip.

A Fresh Start

With his savings of 25 English pounds, Christopher bought some ready-made clothes. He took those clothes and sailed to Philadelphia in 1753. He sold the clothes at a 300% profit. Then he returned to London. He studied the confectionary business for 9 months. This means that he learned how to bake things like cookies and gingerbread.

Baker

In 1754 Christopher returned to Philadelphia. He took several gingerbread prints with him. He could use them to make fancy gingerbread. He set up a bakery business in Laetetia Court. Christopher sold mainly wheat bread and gingerbread. He was the first gingerbread baker in Philadelphia. He bought his flour from the farmers around Lancaster, not from England. People liked him because he was honest and did kind things. His neighbors gave him a nickname. They called him “The Governor of Laetitia Court.”

In 1755 Christopher married Catharine England, whose first husband had died. They had one child. The child only lived a few hours after it was born.

Christopher worked as a baker for over 20 years. During this time he saved and invested his money wisely. By 1774 he owned 9 houses in Philadelphia, a farm near Germantown, and had 3,500 pounds in Pennsylvania money.

Revolution

In 1774 there was much talk of war with England. Christopher was very involved in the affairs of the Revolution. He was elected a member of all of the conventions and committees that met in Pennsylvania in 1774, 1775, and 1776. At one convention, Governor Mifflin asked for people to give money to buy guns. Some people said that no one would contribute. Christopher Ludwick stood up and said,

“Mr. President, I am but a poor gingerbread baker, but put my name down for two hundred pounds.”

In the Army

When an army was formed, Christopher Ludwick volunteered with the flying camp. He took no pay and no food. He encouraged the soldiers by telling them stories of how hard life was in his old country. He said that kings and princes made the lives of the people miserable. Living in their countries was like being a slave. At one time he heard about some soldiers who were thinking of deserting because the food was so poor. Christopher went to them. He told them that the British were like a fire, and they were like a fire brigade. They needed to keep the fire from their town. The men listened to him, and stayed in camp.

Using his Special Skills

The British had a large number of German hired soldiers in their army. These soldiers were called Hessians because they came from the Hesse Darmstadt region of Germany. Christopher Ludwick was born in that same area. He spoke the same dialect that they did. He was very useful as an interpreter. After the battles of Trenton and Princeton there were nearly 1000 Hessian prisoners. Christopher interpreted the American questions for them.

At least once, Christopher Ludwick went undercover. With his commander’s permission, he went to the camp of the Hessian troops near Staten Island. He pretended to be a deserter. He talked with the Hessian soldiers about the differences between their lives and the lives of German people living in America. He told them how much better life could be. Many Hessian soldiers listened to him. Later he escaped from the Hessian camp. His words convinced a number of Hessian soldiers. Gradually, many of them deserted the army and joined the people of Pennsylvania.

Baker General

The Americans were defeated at Brandywine and Germantown. George Washington retreated to Valley Forge. There was not much food. The bread was soggy and tasteless. Some of the bakers who baked for the army were not very honest. George Washington asked Congress to appoint one person to be in charge of all baking for the army. On May 3, 1777, Congress chose Christopher Ludwick They appointed him Superintendent of Bakers, and Director of Baking in the army. John Hancock signed the order. He was the President of Congress at that time. This appointment gave Christopher much responsibility. He was in total charge of all army bakers. He hired them, trained them, paid them, and reported on their progress. Congress asked him to clear up any dishonesty or poor work. His pay was $75 per month, and 2 rations each day.

Congress knew that some bakers had cheated the army in the past. They told Christopher that for every 100 pounds of flour, there should be 100 pounds of bread. Christopher Ludwick refused these conditions. He explained that when yeast and water and other ingredients are added to bread, it becomes heavier. He promised that for every 100 pounds of flour, there would be 135 pounds of bread. Christopher said that he did not want to cheat the government.

Christopher Ludwick traveled from camp to camp, looking for men to train as bakers. He taught the men the trade, and supervised their work. The troops called him the “Baker General.” He managed the bakers so well that the troops never again had to wait for their bread.

The war ended when General Cornwallis surrendered to General Washington. Now the Americans had many prisoners. General Washington ordered six thousand pounds of bread for the British army. He told Christopher to make it good bread. There should be enough so that General Washington could have some if he wanted it.

Character and Appearance

George Washington liked Christopher Ludwick. Christopher often had dinner with General Washington and a large group of men. George Washington would always make a point of speaking to him. A few times he met alone with the General, to discuss the baking department. General Washington often called him “old gentleman.” When they were with other people, Washington called Christopher Ludwick “his honest friend.”

Christopher Ludwick was a tall man. His posture was always very good. He lost an eye through an accident in the war. He had a quick temper, but his anger did not last for long. He was blunt in his manner, but not rude. He was always welcome to eat with the officers wherever he went. He was a sincere patriot and a good storyteller. He could make people laugh. The officers enjoyed his company. He owned a beautiful old china bowl with a silver rim that he had bought in Canton in 1745. He carried this bowl with him, and whenever he drank from it he would say,

“Health and long life

To Christopher Ludwick and his wife."

He always carried a silver coin in his pocket. It had belonged first to his grandfather, and then to his father. His father had given it to him. It had pictures and Bible verses on each side. Christopher carried the coin to remind him of his love for his family and his belief in the goodness of God.

Life after the War

When the war ended, Christopher went back to his farm near Germantown. The British army had taken all furniture, clothing, and valuables. Christopher had very little money. He believed that he should not spend money that he did not have, and did not like to borrow. Because of this, he did without many things. For six weeks after he returned home he slept between blankets because he could not afford sheets. He had been generous in supporting the Revolution. Because of this he had lost a lot of money. The government had paid him in paper money. This money was not worth much. Christopher sold some of his property so that he could buy new clothes and furniture.

Honor from George Washington

George Washington wrote a certificate for Christopher. It meant so much to him that he framed it and hung it on the wall in his parlor. This is what it said:

“I have known Christopher Ludwick from an early period in the war, and have every reason to believe, as well from observation as information, that he has been a true and faithful servant to the public; that he has detected and exposed many impositions, which were attempted to be practiced by others in his department; that he has been the cause of much saving in many respects; and that his deportment in public life, has afforded unquestionable proofs of his integrity and worth.

With respect to his losses, I have no personal knowledge, but have often heard that he has suffered from his zeal in the cause of his country.

Geo. Washington

April 25, 1785”

Later Life

In 1795 his wife Catharine died. She had been a good wife to him, and had supported him in all of his projects. After Catharine died, Christopher sold his farm. He sold all but one of his houses. He put the money from these sales into private bonds and public stock. He rented a room from Frederick Fraley, whom he had trained to be a baker.

Christopher continued to do kind things for other people. Secretly, he would find out who was in need of help, and would quietly provide for their needs. We do not know of all the kind things that he did. We do know that he paid for the freedom of at least 3 African slaves. He also paid for the education of over 50 people. The only person that he would not help was a person who was a drunkard.

During the yellow fever epidemic of 1797, Christopher volunteered in Mr. Fraley’s bakery. He helped make bread to be given to the poor. After the epidemic he moved to the one house he still owned, at 176 North Fifth Street. In 1798 Christopher married Mrs. Sophia Binder. Sophia was a practical woman, who was kind and respectful.

During the last two years of his life Christopher Ludwick was often sick. When he was well, he would read his Bible and other religious books, and visit his friends. After George Washington died, someone wrote a book about his life. Christopher was asked if he would like a copy. He said that he would not. He would soon be dead himself, and, he said,

“I will then hear about it from his own mouth,”

On Monday, June 15, 1801, Christopher developed an infection and a high fever. He died on Wednesday, June 17. He was 80 years old. Christopher Ludwick was buried in the Lutheran Churchyard in Germantown, next to his first wife.

Christopher Ludwick’s Will

In his will, Christopher left amounts of money to family members, and money to various churches and organizations to educate poor children. He left some money to pay the bills of poor hospital patients, and to buy firewood for the poor in Philadelphia. The rest of his estate was left in a fund. This was to be used to start a school to educate poor children from Philadelphia of all nationalities and religions. The will stated that this school must be started within five years.

Where we see his name today

Today the Christopher Ludwick Foundation still supports education in the city of Philadelphia, and gives grants each year.

Reading Level 6.2. Photographs by T. and M. Yates

Christopher Ludwick was born in the town of Griessen in the province of Hesse Darmstadt in Germany on October 17, 1720. His father was a baker. Christopher learned the baking trade as soon as he was old enough to work. When he was 14 he went a free school where he learned to read, write, and work with numbers. He also learned about the Lutheran faith.

Soldier

At age 17 Christopher Ludwick joined the Austrian army as a private. From 1737 to 1740 he fought in the war against Turkey. When the war was over Christopher was part of a group of 100 men who were far from home. They were ordered to march to Vienna across barren, cold country. The march was very hard. On the way 75 of the men died. Christopher was one of the 25 men who lived to reach Vienna. He stayed in Vienna for a few weeks. During that time the Commissary General (man in charge of supplies) for the Austrian Army was executed for being dishonest. This made a big impression on the young man. From Vienna, Christopher traveled to Prague. He was in the town when the French surrounded it. The town was under siege for 17 weeks. Prague surrendered to the French in 1741. When he was free to travel, Christopher joined the Prussian Army.

Sailor and Baker

After a time Christopher had enough of being a soldier. He went to London and took a job as a baker on the ship The Duke of Cumberland. The commander of the ship was Admiral Boscawen. The ship sailed to a number of ports. In 1745 The Duke of Cumberland returned to London. Christopher Ludwick was paid his wages. He received 111 guineas and 1 English crown. Christopher used the money to go back to Germany. He wanted to visit his father. When he reached his home he learned that his father had died. Christopher’s father left him his whole estate. Christopher sold what his father had left him for 500 guilders. He took the money and part of his wages, and went back to London. He decided to enjoy himself. He had a good time, and spent all of his money. When his money was gone, Christopher Ludwick went to sea again. This time he worked as a sailor. His ship sailed from London to Holland, Ireland, and the West Indies. Christopher saved the money he earned on this trip.

A Fresh Start

With his savings of 25 English pounds, Christopher bought some ready-made clothes. He took those clothes and sailed to Philadelphia in 1753. He sold the clothes at a 300% profit. Then he returned to London. He studied the confectionary business for 9 months. This means that he learned how to bake things like cookies and gingerbread.

Baker

In 1754 Christopher returned to Philadelphia. He took several gingerbread prints with him. He could use them to make fancy gingerbread. He set up a bakery business in Laetetia Court. Christopher sold mainly wheat bread and gingerbread. He was the first gingerbread baker in Philadelphia. He bought his flour from the farmers around Lancaster, not from England. People liked him because he was honest and did kind things. His neighbors gave him a nickname. They called him “The Governor of Laetitia Court.”

In 1755 Christopher married Catharine England, whose first husband had died. They had one child. The child only lived a few hours after it was born.

Christopher worked as a baker for over 20 years. During this time he saved and invested his money wisely. By 1774 he owned 9 houses in Philadelphia, a farm near Germantown, and had 3,500 pounds in Pennsylvania money.

Revolution

In 1774 there was much talk of war with England. Christopher was very involved in the affairs of the Revolution. He was elected a member of all of the conventions and committees that met in Pennsylvania in 1774, 1775, and 1776. At one convention, Governor Mifflin asked for people to give money to buy guns. Some people said that no one would contribute. Christopher Ludwick stood up and said,

“Mr. President, I am but a poor gingerbread baker, but put my name down for two hundred pounds.”

In the Army

When an army was formed, Christopher Ludwick volunteered with the flying camp. He took no pay and no food. He encouraged the soldiers by telling them stories of how hard life was in his old country. He said that kings and princes made the lives of the people miserable. Living in their countries was like being a slave. At one time he heard about some soldiers who were thinking of deserting because the food was so poor. Christopher went to them. He told them that the British were like a fire, and they were like a fire brigade. They needed to keep the fire from their town. The men listened to him, and stayed in camp.

Using his Special Skills

The British had a large number of German hired soldiers in their army. These soldiers were called Hessians because they came from the Hesse Darmstadt region of Germany. Christopher Ludwick was born in that same area. He spoke the same dialect that they did. He was very useful as an interpreter. After the battles of Trenton and Princeton there were nearly 1000 Hessian prisoners. Christopher interpreted the American questions for them.

At least once, Christopher Ludwick went undercover. With his commander’s permission, he went to the camp of the Hessian troops near Staten Island. He pretended to be a deserter. He talked with the Hessian soldiers about the differences between their lives and the lives of German people living in America. He told them how much better life could be. Many Hessian soldiers listened to him. Later he escaped from the Hessian camp. His words convinced a number of Hessian soldiers. Gradually, many of them deserted the army and joined the people of Pennsylvania.

Baker General

The Americans were defeated at Brandywine and Germantown. George Washington retreated to Valley Forge. There was not much food. The bread was soggy and tasteless. Some of the bakers who baked for the army were not very honest. George Washington asked Congress to appoint one person to be in charge of all baking for the army. On May 3, 1777, Congress chose Christopher Ludwick They appointed him Superintendent of Bakers, and Director of Baking in the army. John Hancock signed the order. He was the President of Congress at that time. This appointment gave Christopher much responsibility. He was in total charge of all army bakers. He hired them, trained them, paid them, and reported on their progress. Congress asked him to clear up any dishonesty or poor work. His pay was $75 per month, and 2 rations each day.

Congress knew that some bakers had cheated the army in the past. They told Christopher that for every 100 pounds of flour, there should be 100 pounds of bread. Christopher Ludwick refused these conditions. He explained that when yeast and water and other ingredients are added to bread, it becomes heavier. He promised that for every 100 pounds of flour, there would be 135 pounds of bread. Christopher said that he did not want to cheat the government.

Christopher Ludwick traveled from camp to camp, looking for men to train as bakers. He taught the men the trade, and supervised their work. The troops called him the “Baker General.” He managed the bakers so well that the troops never again had to wait for their bread.

The war ended when General Cornwallis surrendered to General Washington. Now the Americans had many prisoners. General Washington ordered six thousand pounds of bread for the British army. He told Christopher to make it good bread. There should be enough so that General Washington could have some if he wanted it.

Character and Appearance

George Washington liked Christopher Ludwick. Christopher often had dinner with General Washington and a large group of men. George Washington would always make a point of speaking to him. A few times he met alone with the General, to discuss the baking department. General Washington often called him “old gentleman.” When they were with other people, Washington called Christopher Ludwick “his honest friend.”

Christopher Ludwick was a tall man. His posture was always very good. He lost an eye through an accident in the war. He had a quick temper, but his anger did not last for long. He was blunt in his manner, but not rude. He was always welcome to eat with the officers wherever he went. He was a sincere patriot and a good storyteller. He could make people laugh. The officers enjoyed his company. He owned a beautiful old china bowl with a silver rim that he had bought in Canton in 1745. He carried this bowl with him, and whenever he drank from it he would say,

“Health and long life

To Christopher Ludwick and his wife."

He always carried a silver coin in his pocket. It had belonged first to his grandfather, and then to his father. His father had given it to him. It had pictures and Bible verses on each side. Christopher carried the coin to remind him of his love for his family and his belief in the goodness of God.

Life after the War

When the war ended, Christopher went back to his farm near Germantown. The British army had taken all furniture, clothing, and valuables. Christopher had very little money. He believed that he should not spend money that he did not have, and did not like to borrow. Because of this, he did without many things. For six weeks after he returned home he slept between blankets because he could not afford sheets. He had been generous in supporting the Revolution. Because of this he had lost a lot of money. The government had paid him in paper money. This money was not worth much. Christopher sold some of his property so that he could buy new clothes and furniture.

Honor from George Washington

George Washington wrote a certificate for Christopher. It meant so much to him that he framed it and hung it on the wall in his parlor. This is what it said:

“I have known Christopher Ludwick from an early period in the war, and have every reason to believe, as well from observation as information, that he has been a true and faithful servant to the public; that he has detected and exposed many impositions, which were attempted to be practiced by others in his department; that he has been the cause of much saving in many respects; and that his deportment in public life, has afforded unquestionable proofs of his integrity and worth.

With respect to his losses, I have no personal knowledge, but have often heard that he has suffered from his zeal in the cause of his country.

Geo. Washington

April 25, 1785”

Later Life

In 1795 his wife Catharine died. She had been a good wife to him, and had supported him in all of his projects. After Catharine died, Christopher sold his farm. He sold all but one of his houses. He put the money from these sales into private bonds and public stock. He rented a room from Frederick Fraley, whom he had trained to be a baker.

Christopher continued to do kind things for other people. Secretly, he would find out who was in need of help, and would quietly provide for their needs. We do not know of all the kind things that he did. We do know that he paid for the freedom of at least 3 African slaves. He also paid for the education of over 50 people. The only person that he would not help was a person who was a drunkard.

During the yellow fever epidemic of 1797, Christopher volunteered in Mr. Fraley’s bakery. He helped make bread to be given to the poor. After the epidemic he moved to the one house he still owned, at 176 North Fifth Street. In 1798 Christopher married Mrs. Sophia Binder. Sophia was a practical woman, who was kind and respectful.

During the last two years of his life Christopher Ludwick was often sick. When he was well, he would read his Bible and other religious books, and visit his friends. After George Washington died, someone wrote a book about his life. Christopher was asked if he would like a copy. He said that he would not. He would soon be dead himself, and, he said,

“I will then hear about it from his own mouth,”

On Monday, June 15, 1801, Christopher developed an infection and a high fever. He died on Wednesday, June 17. He was 80 years old. Christopher Ludwick was buried in the Lutheran Churchyard in Germantown, next to his first wife.

Christopher Ludwick’s Will

In his will, Christopher left amounts of money to family members, and money to various churches and organizations to educate poor children. He left some money to pay the bills of poor hospital patients, and to buy firewood for the poor in Philadelphia. The rest of his estate was left in a fund. This was to be used to start a school to educate poor children from Philadelphia of all nationalities and religions. The will stated that this school must be started within five years.

Where we see his name today

Today the Christopher Ludwick Foundation still supports education in the city of Philadelphia, and gives grants each year.

Reading Level 6.2. Photographs by T. and M. Yates